What it’s like to work on Overwatch’s tools and engine

The world needs heroes now more than ever, it seems. And digital heroes need quite a lot to exist: dramatic motivations, iconic aesthetics, deep designs. But they need code in far greater quantities. Over 2.7 million lines of evolving code power the tools that support Overwatch today.

The Architechs on Overwatch’s engine and tools teams are the keepers of that legacy, and there’s no game without their work.

The Engine Team

Overwatch’s engine team builds the technical infrastructure of the game’s many systems, among them graphics, visual effects, gameplay physics, and audio—the “building blocks” that enable development. Lead Software Engineer Phil Teschner, who worked on the Halo series and Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning before joining Blizzard, is the engine team’s chief block wrangler.

Teschner racked up what he says were “way too many hours” in his journey to play every single Blizzard title before his background in multi-platform and graphics development led him to accept a job here in 2012, working on a new MMO with the codename “Project Titan.” Though Titan was ultimately cancelled, he’s since helped recombine some of its building blocks to ensure that its DNA lives on in Overwatch.

Phil and the rest of the engine team enable Overwatch to run on different platforms (like PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Nintendo Switch) at the best framerate possible. Their work on the code complexities of each piece of hardware lets other Overwatch engineers focus more on development of game features than the engineering implications of various platforms. Like nearly all work on the Overwatch team, this is a thoroughly collaborative effort; Phil notes he “can’t think of any problem where we don’t get together as a group and try to find the way forward.”

Another of the engine team’s responsibilities is tracking and improving performance statistics, memory consumption, patch sizes, and load times, not only for their own sake but also to make room for new features. For example, artists who want to make characters’ skin more realistic, or add new ways to simulate the movement of clothes, work with the engine team to alter those fundamental building blocks without needing to rearchitect the game from the ground up.

Of course, new building blocks still need to be presented to designers, artists and other engineers on the Overwatch team in a usable and efficient way to produce a playable and fun game. That’s where development tools come in.

The Tools Team

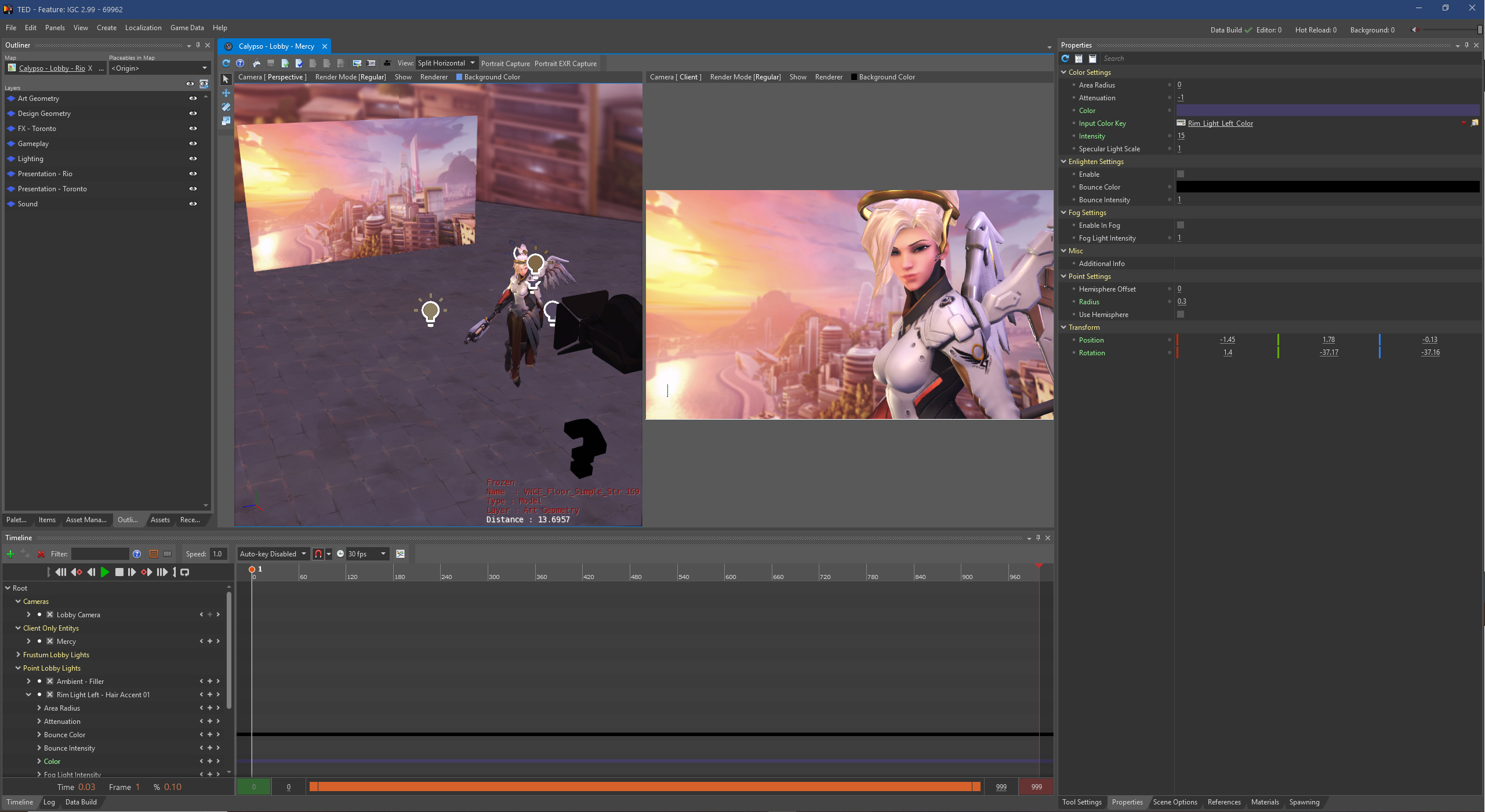

The charge of the Overwatch tools team is “TED,” the game’s editor, a visual interface where artists, designers, and other engineers can arrange and fine-tune those engine building blocks: crafting levels, writing scripts for heroes, adjusting cooldowns, creating the animations and sounds that bring those things to life, and linking it all together. They work with two questions in mind:

1. Where are other members of the team spending most of their time making the game?

2. Can we make that easier and more enjoyable?

Lead Software Engineer Rowan Hamilton, who worked on the Killzone series (and, like Phil, Project Titan prior to Overwatch), made his first game in college. He describes it as “a Diablo clone” and, not coincidentally, blames at least one failed exam on the time he spent playing both Diablo and StarCraft.

Rowan’s guiding principle for the tools team is fitting and succinct: anybody making changes to Overwatch’s gameplay should be able to play through their changes, quickly and often. “The more you enjoy making your game,” Hamilton says, “the better a game you’re likely to make.”

To that end, TED is tailored to the experiences of the developers making Overwatch, built on the lessons the team’s learned over the years. It includes unique processes for modifying content as specific as hero selection or Play of the Game generation, along with representations of Overwatch-specific concepts like skins and team colors.

But TED’s not just for making Overwatch as we know it today; it’s also flexible enough to support creative experimentation around Overwatch’s tomorrows. “Whatever [developers] try,” Hamilton says, “they know we won’t let them break the game, and it’s easy for them to undo work, go back, and take a different approach.” TED’s visualization helps developers see how Overwatch’s 3 million assets and terabytes of source data fit together, enabling them to quickly pull from existing Overwatch components to riff on something familiar… or prototype completely new ideas.

Explosive Horizons

Work on the features that make Overwatch possible isn’t just a process of refining and updating. New tests abound every day, some of them daunting in scope. Development tools and the engine need to support new advances in hardware for Overwatch, and fresh gameplay experiences in Overwatch 2.

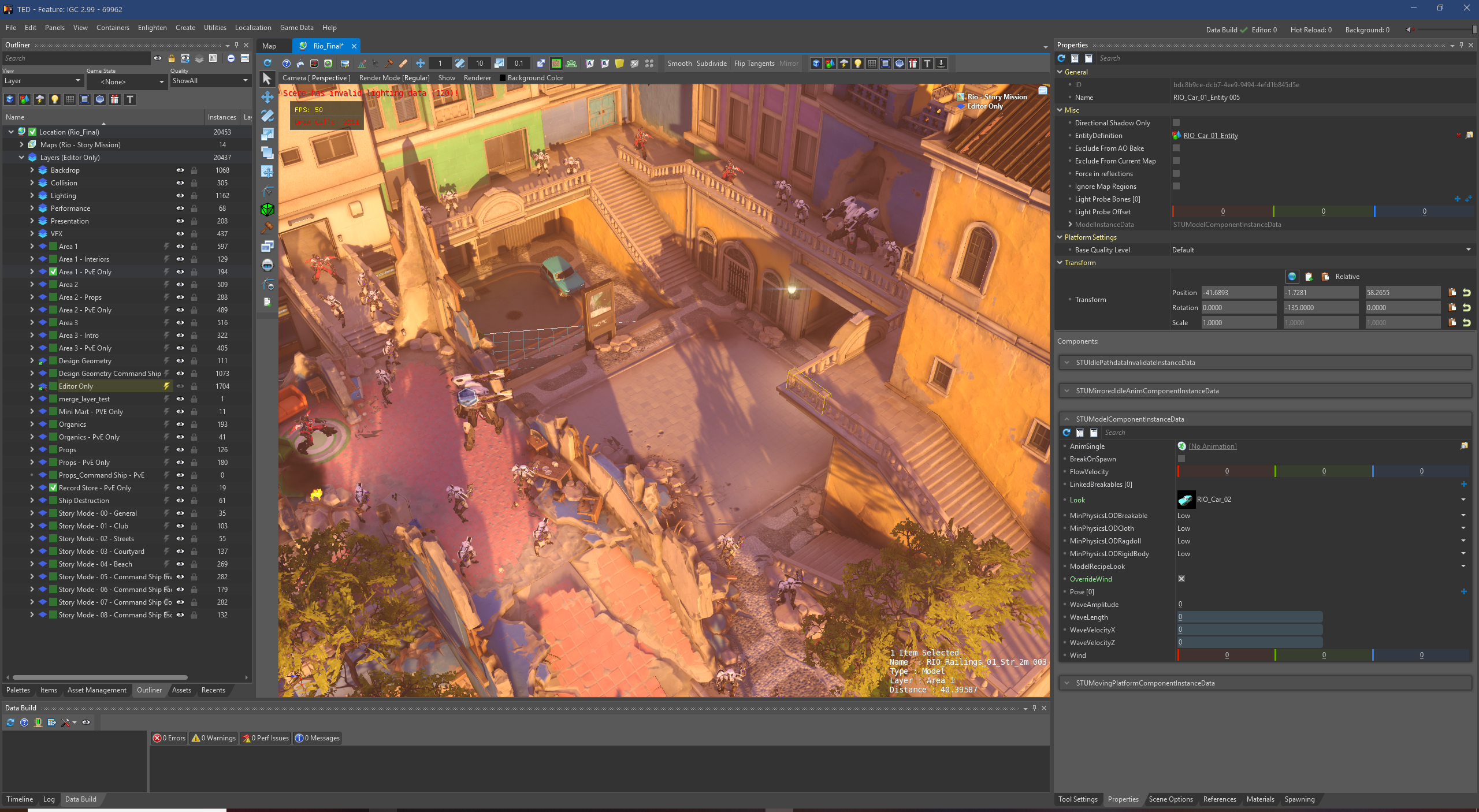

At BlizzCon 2019, the team showcased the first playable build of an Overwatch 2 map—Rio—shared widely outside of Blizzard. But, before Rio appeared on the BlizzCon floor, Phil Teschner and the engine team found themselves at the vanguard of a deceptively straightforward-sounding challenge: the designers wanted to blow up a ship.

This wouldn’t be a tiny setpiece explosion in the sky, but the inside-out destruction of a massive omnic command carrier with Overwatch agents fighting and fires erupting in its belly. Pushing the engine even further, lighting would change throughout the map as the ship’s reactor went critical.

When parts of a level detonate, we expect the way they’re lit to change. In the real world, lighting changes happen over time as visibility shifts and our eyes adjust. The impact of those changes is more apparent closer to light sources, and less evident further away, and a change to lighting in one room can affect lighting in a nearby room.

“Dynamic” real-time lighting like this can be performance-intensive, and transforming lighting across an entire map especially so. Overwatch is built to be played on a variety of systems, so the engine team had to come up with a solution that could enable a big event without hurting the game’s performance.

First, they isolated those dynamic lighting changes to specific parts of the Rio map. Lighting artists placed small probes throughout the in-progress level to identify surfaces that should be “significantly” affected by lighting changes (like a structure fire). Then, the engineers wrote a script to enable dynamic illumination on just those affected surfaces when the ship started exploding, and deactivate it after the event was over.

Overwatch 2’s PvE (Player vs. Environment) maps are larger and more complex than Overwatch maps like Retribution and Storm Rising. That doesn’t just mean more distance to cover, but also longer missions involving more kinds of foes and more elaborate encounters. Adding enemy types leads to complex ability interactions between enemies and heroes–but also between the enemies themselves, like short-range and long-range units that coordinate their attacks.

Designers working in Overwatch’s development tools need a way to visualize a multi-wave encounter that takes place over several minutes. To craft something exciting, they need to be able to preview where an enemy will spawn, and how it will path (move through the level) before an enterprising Overwatch agent takes it out of commission. And, of course, that added complexity needs to carefully manage its impact on the game’s performance.

It’s not a challenge the tools team has completely solved yet, but it’s exactly the kind of problem they assembled to tackle.

How They Work

Tools and engine developers collaborate with other members of the Overwatch team to bring new gameplay elements to life. Crafting any major feature, like the addition of new unit-spawning techniques, starts with a kickoff meeting between gameplay engineering and the designers working on Overwatch’s levels, heroes and abilities to understand both what they’re trying to achieve and how to achieve it. Throughout, the tools team aims to find aspects of those gameplay elements that are painful to build, and prototype until they can make it “trivially easy” to build dozens or hundreds.

Changes to existing features can have huge ramifications, too. When the design team set out to rework Symmetra’s ultimate ability, swapping Teleporter for the present-day Photon Barrier, they knew the projected barrier would need to extend through the entire level to feel like it was powerfully impacting gameplay. Members of the engine team and effects artists worked together to fine-tune the barrier’s look and behavior without introducing unsightly visual problems or performance issues.

The engine team even helps artists and designers refine and enable “crazy ideas” like cloning a hero as an ultimate. They figure out how to make the seemingly impossible possible while working within the constraints of every supported platform, such as defining Echo’s Duplicate ability so that cloned heroes who are eliminated can’t select a new hero (which would require the game to load a 13th).

At the time of writing, the tools and engine teams, like many of us, are working from home—and finding that, despite the distance from their co-workers, they’re closer in some ways. They’re getting together multiple times a week to blow off steam in development playtests, chatting enthusiastically about everything that’s changed or been added since the week before, and using those discussions to refine what they’re doing next.

Phil and Rowan have familiar lists of reasons to like the work they do. Their co-workers are talented and enthusiastic. Everyone on the team has input into significant decisions. They get to contribute to a game that they enjoy playing and building.

But both agree that there’s something particularly special about Overwatch.

Teschner chalks it up to Overwatch’s players. “I’ve worked on a ton of different games, and the way the fan community has responded to the world of Overwatch has been a highlight of my career. The excitement around the game, the fan art we receive, seeing cosplay of our characters—they’ve all been totally new experiences for me."

For Hamilton, who came to Irvine, CA from the Netherlands 7 years ago, the team has become like a family. “I moved across the world to work on this game,” he says. “You develop really close bonds when you’re working on a single product with a close-knit group for that long.”

“I can’t imagine doing anything else with my time.”

The Overwatch team is looking for smart, driven engineers to join the team. Check the career page for more details!